The knock would be stuff of South African cricketing folklore, despite him ending up as a tragic-hero.

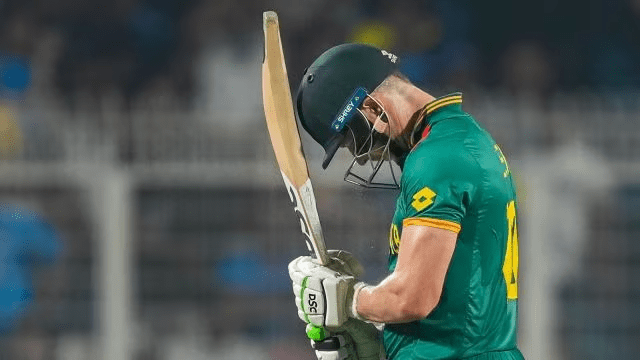

The most enduring David Miller image featured none of the five sixes or eight fours he bludgeoned. Or the wild shriek that accompanied his hundred. It came the ball that ended the innings that would define his career, one that would embody the tragicness of a South African batting hero and his doomed pursuit of an elusive goal.

Miller watched in agony his hit — the bat had slipped off his palms at the point of impact — nestle in Travis Head’s palms. Distraught, he slammed his helmet with the bat, as he staggered back to the pavilion, in the sweat of an attritional hundred and in the tears of failing to guide his team to a bigger score than the 212 they mustered.

It was a rare sight, because Miller is seldom expressive. His father Andrew had once told this newspaper: “You don’t know whether he has scored a hundred or gone for a duck. He won’t brag about a hundred or mourn a zero. He takes both as part of life and moves on.”

But this was different, the stakes were higher than probably any of the games he had ever played. Against Australia. In a World Cup semifinal. The millstone of underachievement tied around the team’s neck and pulling them down with the force of gravitational pull. He was battling the past. The present too — the bowlers and elements, which were tough enough.

When he united with Heinrich Klaasen with South Africa tottering at 24/4 after 11.5 overs, the overhead conditions were sinisterly grey, Josh Hazlewood and Mitchell Starc were whipping up an apocalypse. Miller would have returned to the pavilion first ball, but for the outside edge that fell tantalisingly short of first slip. A few balls later, he almost spooned a catch to Hazlewood at mid-on, but for the ball to drop in front of the fielder and dribble for another four. Pat Cummins grimaced; David Warner snarled. Miller would feel like it was an inescapable crucible of fire.

But he didn’t wither, he didn’t flinch. He knew he is not so much an accumulator as he is an aggressor. But he didn’t let the pressure of dot balls pile on him. He was like a patient birdwatcher, spending hours behind the binoculars, waiting for the bird he wanted to spot. Off the first 28 balls he faced, 18 were dots, but he was still striking at a rate of 95 or thereabouts. His logic in the direst hour was simple— wait for the right ball to strike. Strike he would, eight fours and five sixes, that is 62 off his 101 runs.